What Exactly is SIBO?

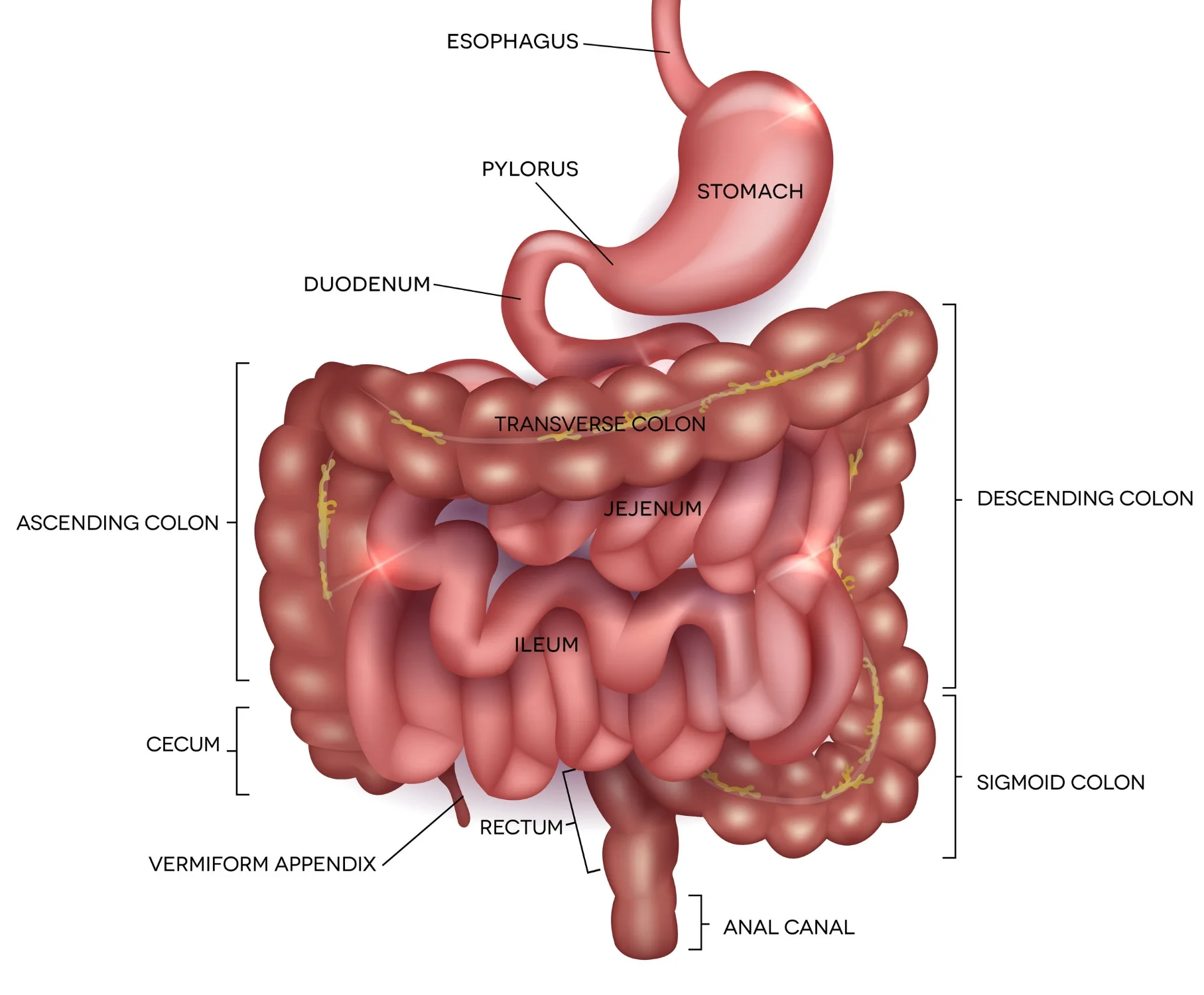

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) is a condition in which an excessive amount of bacteria end up residing within the small intestines. The bacteria that end up overgrowing are typically a combination of bacteria that are normally found in our gastrointestinal tract. However, they should be populating the large intestine in high numbers, and not the small intestines.

Our intestines are divided into two groups – the small intestine, and the large intestine (aka the colon). Food is digested down into its simple, absorbable components in the small intestines, while the waste is pushed into the large intestine for eventual evacuation during bowel movements. In regards to our gastrointestinal bacteria, about 98% of them are meant to reside in our large intestine, while only about 2% in our small intestines. In SIBO, much more than 2% are residing in the small intestine, and this creates havoc with our digestive processes.

COMMON SYMPTOMS

The majority of bacteria in our gastrointestinal system feed on fibers and certain sugars such as lactose (milk sugar) and fructose (fruit sugar). When the bacteria feed, they immediately begin to produce gases such as hydrogen and methane. If SIBO is present, there ends up being an excessive amount of hydrogen and/or methane being produced within the small intestines, which leads to the following symptoms as the small intestines expand:

- Abdominal bloating/distension

- Excessive belching

- Excessive flatulence

- Abdominal pain/cramping

- Diarrhea or constipation or alternating between both

- Nausea

- Heartburn

These are the typical symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Research over the last 15 years has shown a major connection between SIBO and IBS. Specifically, up to 84% of IBS cases will test positive for SIBO. And when you treat the SIBO, the IBS goes away. Therefore, SIBO is now considered the #1 root cause behind IBS.

CAUSES OF SIBO

The primary reason why people end up with SIBO is because of a dysfunctional migrating motor complex (MMC). The MMC creates high intensity and high frequency smooth muscle contractions of the intestines to push waste from the small intestines into the large intestine. These contractions that occur every 3 – 4 hours throughout the day also ensure to sweep bacteria from the small intestines into the large intestine, while also forcing bacteria to remain in the large intestine. Therefore, if the MMC is dysfunctional, the sweeping of the small intestines is not as effective, and bacteria can then begin to over grow in the small intestines and SIBO can develop.

The primary cause of a dysfunctional MMC is an autoimmune cross-reaction that occurs after a case of food poisoning or traveler’s diarrhea. 1 in 5 people end up with this cross-reaction, which helps to explain why cases of IBS due to SIBO are so common.

Other compounding factors that can lead to SIBO are low stomach acid, bile insufficiency, intestinal strictures, opiate medication use, and MMC changes due to Celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

In conclusion, SIBO is the primary cause of IBS symptoms. And with proper assessment via a hydrogen and methane breath test, SIBO can be effectively and efficiently treated and prevented in the future. Contrary to what many doctors say, most cases of IBS truly do have a known cause, and therefore, a known treatment that does more than just manage symptoms. Treat the root cause behind your IBS today.

ASSOCIATED CONDITIONS

As a common underlying cause, SIBO is associated with many other health complaints and conditions. SIBO is either correlated with causing the conditions below, or is thought to be partly caused by these conditions. The list may be large, but if you experience digestive disturbances and one or more of the conditions listed, SIBO testing is warranted. By treating the root cause, patients can experience a permanent shift in their health.

- Acne Roseacea

- Acne Vulgaris

- Acromegaly

- Alcohol Consumption (moderate intake)

- Anemia

- Atrophic Gastritis

- Autism

- Celiac Disease

- Cystic Fibrosis

- Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

- Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

- Chronic Medication Use

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPI's)

- Opiates (pain medication)

- NSAID's (anti-inflammatory medications such as Advil/Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Motrin, etc.)

- Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT)

- Diabetes

- Diverticulitis

- Dyspepsia

- Ehlers-Dalos Syndrome

- Environmental Enteric Dysfunction

- Erosive Esophagitis

- Fibromyalgia

- Fructose Malabsorption

- Gallstones

- Gastrointestinal Cancer

- Gastroparesis

- GERD (Reflux)

- HIV

- Hepatic Injury (Liver Injury)

- History of Surgery

- Any Abdominal Surgery

- Post Gastrectomy (Stomach removal)

- Post Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Surgery

- Post Cholecystectomy (Gallbladder removal)

- Post Colorectal Cancer

- H. Pylori Infection (Ulcers)

- Hypochlorhydria (low stomach acid)

- Hypothyroidism/Hashimoto's Thyroiditis

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) including Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Interstitial Cystitis

- Lactose intolerance

- Leaky Gut Syndrome

- Liver Cirrhosis (Liver Damage)

- Lyme Disease

- Malabsorption Syndrome

- Muscular Dystrophy (Myotonic Type 1)

- Myelomeningocele (Spina Bifida)

- Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis

- Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

- Obesity

- Pancreatitis

- Parasites

- Parkinson's Disease

- Pernicious Anemia

- Prostatitis, chronic

- Radiation Enteropathy

- Restless Leg Syndrome

- Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

- Scleroderma (Systemic Sclerosis)

- Short Bowel Syndrome

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) (includes Concussions)

- Tropical Sprue

- Whipple's Disease

REFERENCES:

Pimentel, M., Chow, E., & Lin, H. (2000). Eradication of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 95(12), 3503-3506.

Pimentel, M., Chow, E., & Lin, H. (2003). Normalization of lactulose breath testing correlates with symptom improvement in irritable bowel syndrome: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. The American Journal of Gastroenterology Am J Gastroenterology, 98, 412-419.

Wigg, A., Roberts-Thomson, I., Dymock, R., McCarthy, P., & Grose, R. (2001). The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, intestinal permeability, endotoxaemia, and tumour necrosis factor alpha in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Gut, 48, 206-211.

Parodi, A., Paolino, S., Greco, A., Drago, F., Mansi, C., Rebora, A., . . . Savarino, V. (2008). Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Rosacea: Clinical Effectiveness of Its Eradication. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 6(7), 759-764.

Lin HC, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a framework for understanding irritable bowel syndrome. JAMA. 2004 Aug 18;292(7):852–858.

Pyleris E et al. The prevalence of overgrowth by aerobic bacteria in the small intestine by small bowel culture: relationship with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2012 May;57(5):1321–1329.

Pimentel M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Normalization of lactulose breath testing correlates with symptom improvement in irritable bowel syndrome. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 Feb;98(2):412–419.

Klaus J et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth mimicking acute flare as a pitfall in patients with Crohn's Disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009 Jul 30;9:61.

Rubio-Tapia A, et al. Prevalence of small intestine bacterial overgrowth diagnosed by quantitative culture of intestinal aspirate in celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009 Feb;43(2):157–161.

Bures J. 2010 Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Jun 28;16(24):2978–2990.

Roland BC. Low ileocecal valve pressure is significantly associated with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). Dig Dis Sci. 2014 Jun;59(6):1269–1277.

Khoshini R, Dai SC, Lezcano S, Pimentel M. A systematic review of diagnostic tests for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Dig Dis Sci. 2008 Jun;53(6):1443–1454.

Rodríguez LA. Ruigómez A. Increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome after bacterial gastroenteritis: cohort study. BMJ. 1999 Feb 27;318(7183):565–566.

Beatty JK. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome: mechanistic insights into chronic disturbances following enteric infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Apr 14;20(14):3976–3985.

Zanini B. Incidence of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome and functional intestinal disorders following a water-borne viral gastroenteritis outbreak. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Jun;107(6):891–899.

Hanevik K. Development of functional gastrointestinal disorders after Giardia lamblia infection. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009 Apr 21;9:27.

Pokkunuri V. Role of cytolethal distending toxin in altered stool form and bowel phenotypes in a rat model of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012 Oct;18(4):434–442.

Sung J et al Effect of repeated Campylobacter jejuni infection on gut flora and mucosal defense in a rat model of post infectious functional and microbial bowel changes. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013 Jun;25(6):529–537.

Pimentel M et al. Autoimmunity links vinculin to the pathophysiology of functional bowel changes following Campylobacter jejuni infection in a rat model. Dig Dis Sci. Epub 2014 Nov.

Youn YH, Park JS, Jahng JH, et al. Relationships among the lactulose breath test, intestinal gas volume, and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2011 Jul;56(7):2059–2066.

Pimentel M, Mayer AG, Park S, Chow EJ, Hasan A, Kong Y. Methane production during lactulose breath test is associated with gastrointestinal disease presentation. Dig Dis Sci. 2003 Jan;48(1):86–92.

Pimentel M, Lin HC, Enayati P, et al. Methane, a gas produced by enteric bacteria, slows intestinal transit and augments small intestinal contractile activity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006 Jun;290(6):G1089–G1095.